CT

Case Report: It’s a Small Whirl Afterall

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21980/J83S8GThe CT imaging of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated multiple loops of dilated small bowel with a whirl sign (red arrow) within the mid abdomen and a transition point (green arrow), suspicious for closed loop bowel obstruction and internal hernia.

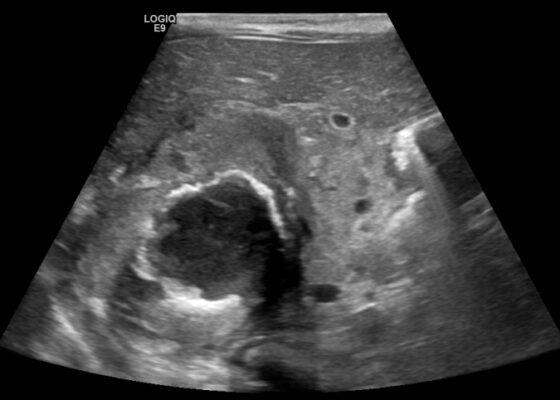

Ovarian Juvenile Granulosa Cell Tumor Case Report

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21980/J8035HA focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) exam was performed initially to evaluate for intra-abdominal injury given the clinical picture. A phased-array ultrasound transducer was placed in sagittal orientation along the patient’s right and left flank, demonstrating extensive heterogenous fluid collections in Morrison’s pouch (red arrow), subphrenic space (solid green arrow), and splenorenal recess (dashed green arrow). To further evaluate, a phased-array transducer was placed over her pelvic area in transverse orientation, demonstrating, a large, heterogeneous mass (outlined in yellow arrows). The surgical team was promptly consulted and blood products were ordered. Although there was concern for impending hemorrhagic shock due to patient’s presenting tachycardia, the patient was hemodynamically stable enough for a CT scan of her chest, abdomen, and pelvis. The CT scan showed large-volume ascites, which exerted mass effect on all abdominal organs with centralization of bowel loops. Additionally, there was a large, 6.4 x 6.8 x 10.9-centimeter, midline pelvic mass (outlined in blue arrows).

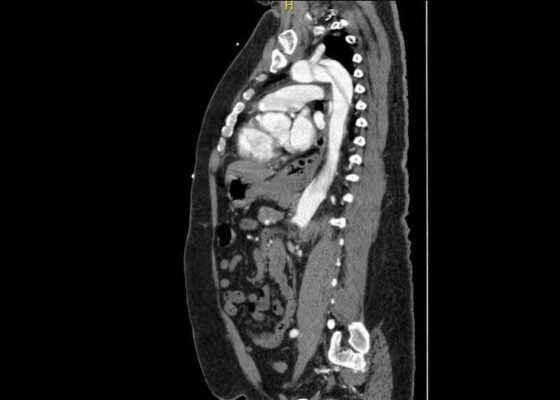

A Case Report of Aortic Dissection Involving the Aortic Root, Left Common Carotid Artery, and Iliac Arteries

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21980/J8V93KComputed tomography angiography (CTA) of the thoracic and abdominal aorta revealed an aortic dissection of the ascending aorta, with a dissection flap starting from the aortic root/aortic annulus (yellow arrows), extending into the aortic arch (light blue arrowhead) and involving the left common carotid artery (purple arrow), left subclavian artery (pink arrow), extending to the descending aorta (red arrows), and into the bilateral iliacs (green arrows). The true lumen (red star) and false lumen (blue star) created by the dissection flap can best be seen in the axial views.

A Case Report of Epiglottitis in an Adult Patient

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21980/J8QM09At the time of presentation to the ED, laboratory results were significant for leukocytosis to 11.8 x 109 white blood cells/L and a partial pressure of carbon dioxide of 52 mmHg on venous blood gas. Computed tomography (CT) of the soft tissue of the neck with contrast showed edematous swelling of the epiglottis and aryepiglottic fold with internal foci of gas (blue arrow) and partial effacement of the laryngopharyngeal airway and scattered cervical lymph nodes bilaterally (Figure 1). Findings were consistent with epiglottitis containing nonspecific air. Additionally, the pathognomonic “thumbprint sign” (yellow arrow) was found on lateral x-ray of the neck (Figure 2). The CT findings as shown in figure 3 illustrate lateral view of the swelling of the epiglottis, gas, and blockage of the airway.

An Atraumatic, Idiopathic Case Report of Intraperitoneal Bladder Dome Rupture

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21980/J85S83On regular CT scan imaging, the urinary bladder is partially distended with contrast with no focal wall thickening or intraluminal hematoma. There is an intraperitoneal bladder rupture with site of rupture likely at the dome of the bladder. The bladder is outlined in red, and the bladder rupture boundaries are outlined in yellow, showing the urine as free fluid escaping into the intraperitoneal space. We also provide these findings in an axial CT in video format. On CT cystography, there is a significant amount of contrast-enhanced urine noted within the visualized peritoneal spaces. The small amount of air present anteriorly is related to the catheterization because a Foley balloon is present within the bladder. These findings are annotated with the peritoneal spaces outlined in yellow, the air in the blue outline, and the bladder in the red outline. All of these CT cystography findings are also presented in an axial view in video format.

Case Report of an Empyema Identified on Lung Ultrasound

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21980/J8SH2NUsing a curvilinear ultrasound probe, images of the patient were obtained from the left mix-axillary line. These images demonstrate a loculated left-sided pleural effusion (outlined in the attached ultrasound image in blue) that was moderate in size, concerning for an empyema. The diaphragm on the right (red) of the image outlines the inferior margin of the collection of pus, which is seen in the inferior aspect of the left lung. Unfortunately, rib shadows on the left side of the image prevent the full empyema from being captured in this single image. As a result of the bedside ultrasound, however, the patient was rapidly diagnosed with an empyema and was initiated on antibiotics, which is further discussed below. After his bedside ultrasound was completed, his chest x-ray revealed the expected left-sided pleural effusion. Additionally, a CT angiogram of the chest was ordered to rule out a pulmonary embolism, which was negative for an embolism but does redemonstrate the left-sided loculated pleural effusion (outlined on the CT axial and coronal images in blue).

A Case Report of Neonatal Vomiting due to Adrenal Hemorrhage, Abscess and Pseudohypoaldosteronism

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21980/J8QQ0BAn ultrasound (US) of the abdomen was obtained to evaluate for possible pyloric stenosis (see US transverse/dopper imaging). While imaging showed a normal pyloric channel, it revealed an unexpected finding: a complex cystic mass arising from the right adrenal gland (yellow outline), measuring 5.8 by 4.0 by 6.4 cm with calcifications peripherally and mass effect on the kidney without evidence of vascular flow (blue arrow). Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen/pelvis with IV contrast was subsequently obtained and measured the lesion as 2.8 by 4.6 by 4 cm without evidence of additional masses, lymphadenopathy or left adrenal gland abnormality (see CT axial, coronal, and sagittal imaging).

Case Report of Unusual Facial Swelling in an 8-Month-Old

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21980/J8M06FFacial ultrasound revealed local inflammatory changes such as increased echogenicity and heterogeneity in the soft tissues of the right cheek, suggestive of soft tissue edema. There was evidence of a prominent right parotid gland with increased heterogeneity suggestive of a traumatic injury. Additionally, facial ultrasound demonstrated a 6mm ill-defined anechoic collection within the right cheek without increased doppler flow (green arrow), thought to represent a focal area of edema instead of an abscess.